Small and nocturnal hedgehogs can be identified by their spiky coats. These animals are members of the Erinaceidae family, which is further subdivided into the Soricinae (shrews) and Erinaceinae (hedgehogs). Native to Europe, Asia, and Africa, hedgehogs may be found in a variety of natural settings, including gardens, woodlands, savannahs and deserts, depending on the species.

Our journey encompasses both the visible and hidden aspects of their structure, from the external features that characterize their unique appearance to the internal systems that sustain life. We’ll examine the skeletal framework that provides support and protection, along with the sensorial and nervous systems that enable hedgehogs to interact with their environment with remarkable efficiency.

Our discussion will also extend to the digestive system, highlighting how hedgehogs process their varied diet and reproductive anatomy, shedding light on their continuation as a species. Additionally, we’ll explore the phenomenon of hibernation, a critical aspect of their lifecycle that allows them to survive adverse conditions. Through this comprehensive analysis, we aim to gain a deeper understanding of the hedgehog anatomy at a glance and its adaptations to the natural world.

Table of Contents

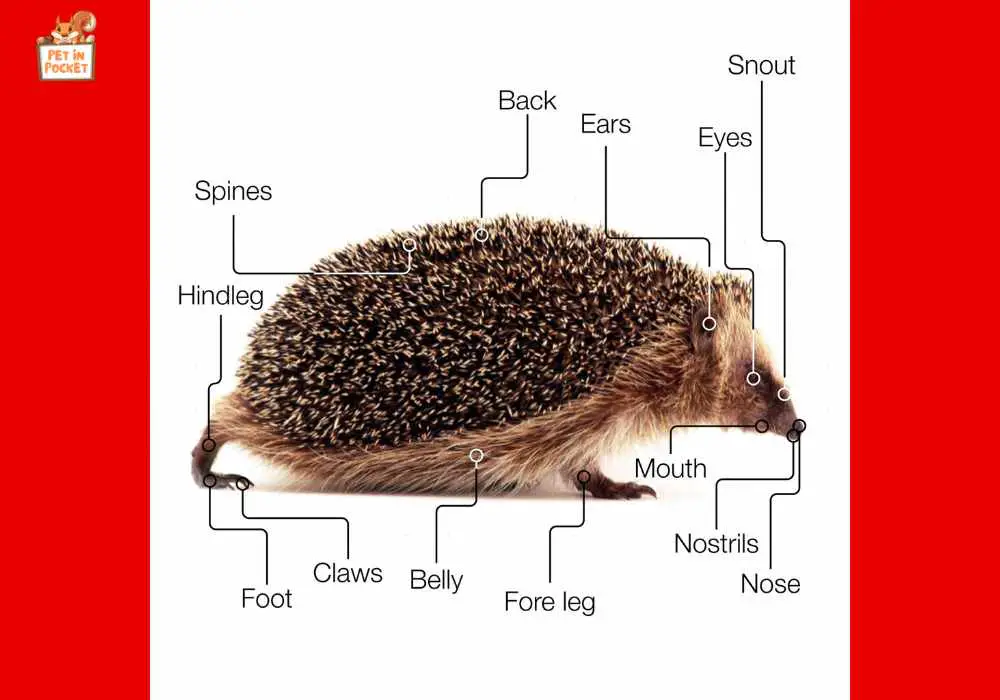

External Anatomy of a Hedgehog

Hedgehogs outside of the body are quite fascinating. Here’s an overview of the key features of a hedgehog’s external anatomy:

Quills

Hedgehog quills, commonly called “spines” or “needles,” are modified keratin hairs like human hair and nails. Hedgehogs’ quills are their primary protection against predators. In contrast to porcupine quills, hedgehog quills are securely adhered to a predator’s skin and cannot readily be removed. Hedgehog quills are hollow and have intricate architecture with bands surrounding them for strength and flexibility. For defence, the hedgehog may extend its quills, anchored in muscles, making it seem more significant and more frightening. This is “spiking up.” Most predators avoid hedgehogs that roll into balls because their quills protect them.

Hedgehogs are born with soft quills covered by a membrane that dries and shrinks, enabling them to emerge without injuring the mother. Young hedgehog quills harden within hours. In a process called “quilling,” hedgehogs lose their young quills and develop adult ones. Hedgehogs, like newborns, may be stressed and unpleasant during teething.

What Hedgehog Quills Are Made Of

Keratin, a potent protein, forms hedgehog quills. This protein is the quill’s foundation, giving it the power to face predators. A flexible, softer keratin core lies underneath the quills. This weaker inner core allows the quills to bend without breaking, giving the hedgehog great strength.

The amount and lifetime of hedgehog quills are intriguing. The average hedgehog has 5,000 to 7,000 quills on its back. Hedgehogs lose and regrow quills. This cycle of loss and regeneration keeps the hedgehog’s defences sharp and ready to defend it at any time. This dynamic process shows hedgehogs’ flexibility and tenacity, making their quills vital to survival.

Size and Body Shape

So, what is the size and shape of a hedgehog’s body? Hedgehogs are mostly known for their unique round bodies, which include a short tail and a pointed snout. These features allow them to coil into a tight ball to protect themselves from predators. From tail to snout, hedgehogs measure 20–30 centimetres (8–12 inches). Depending on the species and age, a hedgehog’s weight may vary considerably; for example, a 400-gram (or 14-ounce) hedgehog can weigh up to 2.2 pounds (1 kilogram) in more prominent species. These animals have comparatively short limbs, and their powerful, clawed feet are used for digging. Despite their aptitude for racing and climbing, hedgehogs are essentially creatures that stay on the ground.

Sensory Capabilities:

Vision

Hedgehogs have a vision adapted to low-light conditions, typical of their nocturnal lifestyle. However, their ability to see fine details is limited. Instead, their eyes are better suited to detecting movement and general shapes, which helps them avoid predators or spot the movements of prey in the dark. Their retinas are likely dominated by rod cells, which are more sensitive to light than cone cells, which are responsible for colour vision in bright light conditions.

Hearing

Hedgehogs can hear many sounds due to their keen hearing.

This acute sense is vital for communication, hunting, and predator avoidance. Hedgehogs can hear the rustling of insects in the underbrush, which they prey upon and the approach of potential predators. Their large, movable ears can swivel to pinpoint the direction of sounds, enhancing their auditory perception.

Smell

A hedgehog’s sense of smell is perhaps its most critical sensory tool. They rely on their olfactory abilities to find food, identify potential mates, and detect danger. Their noses are constantly in motion as they sniff their way through their environment. Their acute sense of smell guides them to insects, worms, and other minute invertebrates to compensate for their poor eyesight.

Touch

The spines of a hedgehog, while primarily serving as a defence mechanism, are also sensitive to touch. They can detect pressure and vibrations, alerting the hedgehog to nearby movements. The skin beneath the spines, along with the hedgehog’s face, legs, and underbelly, is also sensitive, allowing the hedgehog to navigate its environment, avoid obstacles, and engage with other hedgehogs.

Nervous System of a Hedgehog

Brain

The brain of a hedgehog, while small, is complex enough to process the vast amount of sensory information it receives, particularly from its olfactory and auditory systems. The areas of the brain associated with these senses are more developed, enhancing their ability to process smells and sounds. This is crucial for a nocturnal animal that relies heavily on these senses for survival.

Spinal Cord

A lot of information goes to and from the brain through the spinal cord.

It’s responsible for reflex actions, such as the automatic curling into a protective ball when a hedgehog senses a threat. This reflex is vital for a hedgehog’s defense mechanism, allowing it to protect its vulnerable underbelly and face by presenting a spiny exterior to potential predators.

Peripheral Nervous System (PNS)

Hedgehog PNS nerves connect the spinal cord to the body, enabling sensory input and motor output. Sensory nerves convey touch and olfactory impulses from the spines and nose to the brain. On the other hand, motor nerves deliver commands from the brain to the muscles, controlling movements ranging from the twitch of a nose while sniffing to the rapid curling into a ball when startled.

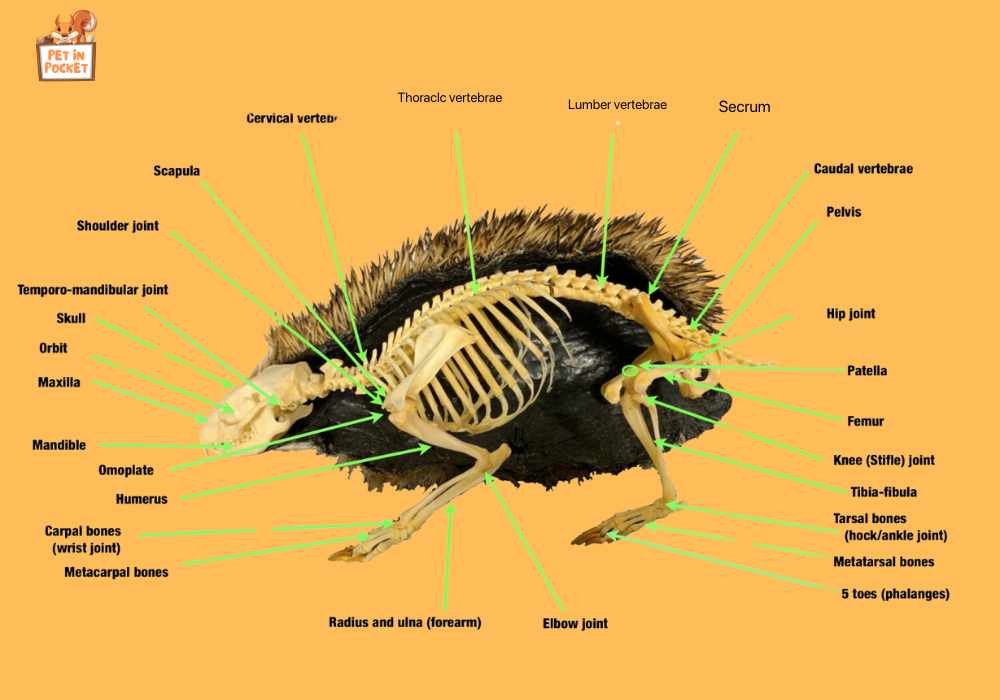

Skeletal structure of a hedgehog

A hedgehog’s skeleton is precisely built to support its lifestyle of foraging, burrowing, and rolling into a ball to avoid predators. Here is the explained detail:

Scapula

The scapula, also called the shoulder blade, is a bone part of the shoulder girdle in mammals, including hedgehogs. In hedgehogs, as in other mammals, the scapula is a flat, triangular-shaped bone on the rib cage’s dorsal side. It serves as an essential attachment site for muscles that facilitate the movement of the forelimbs.

Maxilla

An upper jawbone that contains top teeth is a hedgehog’s maxilla. Supporting the nose and eye sockets is essential to the mouth and face. Hedgehogs’ maxillas support their teeth for eating insects, worms, and other tiny animals and are tailored to their nutritional and sensory demands. Their distinctive snouts and sensitive whiskers help hedgehogs forage and navigate, while the maxilla adds to their face anatomy.

Mandible

A hedgehog’s lower jawbone is called the mandible, an essential part of its head. Like in other animals, the hedgehog’s jaw holds its teeth in place and is an integral part of how it eats. It is important to note that hedgehogs eat insects as their primary food source. Their mouths are designed to help them find, catch, and eat their meal. The hedgehog needs to be able to dig and burrow in order to stay alive in its natural environment. The mandible’s strength and movement also help it do these things. Along with the rest of the hedgehog’s skeletal system, the jaw is built to support its unique eating habits and way of life.

cervical vertebrae

Hedgehogs and other animals both have vertebrae in their necks. These are called cervical vertebrae. Regarding animals, the cervical vertebrae are usually small and flexible, which lets the head move in many different ways. Because hedgehogs are animals, they have seven cervical vertebrae, the same number people have.

The skull is supported by these vertebrae, which also protect the spinal cord and allow blood to flow to the brain through vertebral arteries that go through unique holes called foramina. The first two vertebrae in the neck called the atlas and axis, are designed to let the head move back and forth and tilt. The rest of the cervical vertebrae are less specialized, but they are still crucial for supporting the neck and letting it move.

The way hedgehogs live and what they need from their bodies affects the shape of their neck vertebrae. Even though hedgehogs are mammals, they may have evolved in specific ways that allow them to curl into a ball to protect themselves. This requires a robust and flexible neck so the hedgehog can tuck its head under its body and cover it with spines.

Thoracic and lumbar vertebrae

The thoracic vertebrae of a hedgehog, similar to other mammals, are part of the vertebral column located between the cervical (neck) vertebrae and the lumbar (lower back) vertebrae. These vertebrae support the hedgehog’s rib cage. They are integral to its skeletal structure, providing attachment points for ribs and muscles, hence playing a crucial role in the protection of the thoracic organs (like the heart and lungs) and in respiratory movements.

Like in other animals, a hedgehog’s thoracic vertebrae are part of the spinal column and are situated between the cervical (neck) vertebrae and the lumbar (lower back) vertebrae. These vertebrae support the hedgehog’s rib cage and are an important part of its spinal system. They give the ribs and muscles places to connect, protecting the thoracic organs (like the heart and lungs) and helping the animal breathe. In general, hedgehogs have 13 thoracic vertebrae.

Lumbar vertebrae are in the lower back, below the thoracic vertebrae and above the sacrum of the spine. Lumbar vertebrae are bigger and stronger than thoracic vertebrae and lack ribs. Their major job is to support the body and move the lower back. Hedgehogs’ lumbar vertebrae help them coil, dig, and navigate.

Sacrum

Like other mammals, The hedgehog’s sacrum connects the lumbar vertebrae to the tail vertebrae and pelvis in the lower spine. In mammals, the sacrum is made of united vertebrae. This fusion stabilizes the pelvis, supporting the animal’s weight and allowing mobility. Like many tiny animals, Hedgehogs depend on their sacrums to support the spine and connect hip and rear leg muscles. While hedgehogs and other animals have distinct sacrum vertebrae, their major purpose is to link the spine to the pelvis and facilitate locomotion and weight-bearing.

Pelvis

The hedgehog pelvis is vital to its lower body skeleton, providing several functions. It supports the spinal column, helping the hedgehog maintain its form. The reproductive and excretory organs are protected by this bony structure. The hedgehog’s hind limbs need attachment places for mobility and support. Several pelvic muscles let hedgehogs move and curl into a ball for safety when attacked. In female hedgehogs, the pelvis is important for reproduction and birthing. The hedgehog’s pelvis fits its lifestyle, nutrition, environment, and defence systems, allowing it to coil into a ball and reveal its spiky back to predators while covering its softer underparts.

Hip Joint

Mammals, including hedgehogs, have hip joints that are made up of a ball and a hole. These joints connect the back leg to the pelvis. The rounded head of the femur (thighbone) goes into the acetabulum, a cup-shaped opening in the hip. This joint lets the thighbone move in many directions. Flexible joints like these let hedgehogs walk, run, and, in the case of hedgehogs, curl up into a ball for safety.

Patella

The patella is a tiny bone in front of the knee joint in many vertebrates, including mammals. In the context of a hedgehog, the patella is part of its hind limb skeletal structure. This fulcrum boosts the leverage of the quadriceps femoris tendon, the big muscle at the front of the thigh, and is vital to knee mechanics.

Femur

Hedgehogs, famed for their spiky coats, have thigh bones called femurs. This bone connects the pelvis to the knee in the hind limbs. Hedgehogs’ femurs support their locomotor muscles, like other mammals. Tiny hedgehogs have tiny femurs compared to bigger mammals. A hedgehog’s femur has a head, shaft, and distal end that links the lower leg bones at the knee, like other mammals. Hedgehogs forage for food and curl into balls for safety; thus, their femurs are shaped and sized for them.

Tibia-fibula

The tibia, often known as the shinbone, is the bigger and more medial bone. It carries most of the body’s weight and is essential to the knee and ankle joints. Leg and foot muscles and ligaments link to the tibia. The fibula is the lower leg’s smaller lateral bone. Compared to the tibia, it is light. The fibula stabilizes the ankle and attaches the foot and toe muscles. The fibula stabilizes the tibia and strengthens the lower leg.

Tarsal Bones

Similar to other mammals, hedgehogs have tiny tarsal bones in their rear foot, notably in the ankles. These bones help the hedgehog move and support its legs. The calcaneus, or heel bone, is the biggest tarsal bone and connects calf muscles. The talus, above the calcaneus and below the tibia and fibula, forms the lower ankle joint. The cuboid bone is on the lateral foot, while the navicular lies in front of the talus. Along with the smaller cuneiform bones, these tarsal bones help the foot structure and function for hedgehogs’ walking, running, and digging.

Phalanges

When you look at a hedgehog, the small bones that make up its toes are called phalanges. In animals, phalanges are part of the leg bones and are very important for many things, like moving and gripping. Like humans, hedgehogs have five toes on each foot. Each toe has phalanges, which are like fingers and toes. The amount and order of phalanges in each hedgehog species’ toe can be different, but in general, they follow the pattern of phalangeal bones in mammals. The hedgehogs need these bones to dig, find food, and get around in their surroundings.

Elbow Joint

Hedgehogs have hinge synovial elbow joints that link the upper arm to the forearm. Hedgehogs have short, compact limbs for digging and burrowing, including this joint. The hedgehog can dig tunnels, forage for food, and curl up into a ball for safety because the elbow joint bends and straightens the forearm.

This joint has three bones: the upper arm humerus, the forearm radius, and the ulna. These bones are linked by ligaments and muscles for movement. A membrane encases the joint, secreting synovial fluid to reduce friction.

Forearm

What a hedgehog calls the part of its front arms that goes from the elbow to the wrist is its forearm. Hedgehogs are small animals that are known for having fur with spines. Their limbs, even their wrists, are small and strong because they are better at digging and burrowing than running long distances or climbing. The forearm has bones like the radius and ulna found in human arms, but they are much more compact. The hedgehog’s wrist muscles and structure allow it to do things necessary for its survival, like searching for food, making eggs, and digging holes for protection.

Humerus

The humerus, like the upper arm bone in humans, is found in most vertebrates, including hedgehogs. The hedgehog’s forelimb skeleton includes the humerus, which connects the shoulder to the elbow. Forelimb muscles join to it, allowing the hedgehog to sprint.

Hedgehog anatomy of digestion

The hedgehog’s digestive system is made up of the following parts:

The mouth and teeth

The first thing a hedgehog does to digest food is break it up into smaller pieces that are easier to swallow. The sharp incisors help hedgehogs cut, the pointed canines help them grab, and the flat premolars and molars help them grind. Their diverse diet means that this tooth arrangement helps them eat animal and plant food well.

Esophagus

The muscular esophagus joins the mouth and stomach. It moves chewed food to the stomach by peristalsis. These involuntary movements ensure that food is moved efficiently towards the stomach, regardless of the hedgehog’s orientation.

Stomach

Food is mixed with gastric acids and digesting enzymes in the stomach. These break down proteins and turn solid food into chyme, a semi-solid mixture. The acidic environment in a hedgehog’s stomach makes it very good at breaking down the chitin in the exoskeletons of insects, which are a regular part of their food.

Small Intestine

The duodenum, jejunum, and ileum make up the small intestine, which absorbs nutrition. In the duodenum, pancreatic and liver digestive fluids help digest fats, proteins, and carbs. After digesting nutrients, the jejunum and ileum absorb them into the circulation.

Large Intestine

The large intestine’s main role is to absorb water and electrolytes from the indigestible matter, forming solid waste. Although the cecum in hedgehogs is not as developed as in some other animals, it may still contribute to the fermentation process of undigested fibers. The conservation of water through reabsorption in the large intestine is crucial for hedgehogs, especially in drier habitats.

Anus

The anus is where processed food is discharged as faeces. The ability to control the expulsion of waste is vital for maintaining hygiene, particularly since hedgehogs can curl into a ball, potentially bringing them into close contact with their own waste.

Reproductive Anatomy of a Hedgehog

The reproductive systems of male and female hedgehogs are different. Here’s the details:

Male Hedgehog Reproductive Body Parts

For male hedgehogs, the intimate parts are on the outside. The penis sits near the middle of the torso and is the most visible part. It can look like either a belly button or a navel, which can cause misunderstanding. This centre position isn’t very common for animals. The testes are inside and can’t be seen outside because they don’t go down into the scrotal sacs like in many other animals.

The reproductive anatomy of a female hedgehog

The vulva, or sexual organ, of a female hedgehog, is found near the base of the tail. This is a feature shared by many animals. Inside, they have two uteri (bicornuate uterus), a trait of some animal species that lets them carry more than one baby. As placental animals, hedgehogs have bodies that are designed to help females give birth to live young.

Process of Reproduction

Hedgehogs usually live alone, but when it’s time to breed, they look for mates. The female goes through a pregnancy that lasts about 35 to 40 days after mating. Hedgehogs can have more than one litter or group of babies. These are called hoglets. Hoglets are born blind and have soft spines that get tougher after a few hours.

Hibernation and Aestivation

Hibernation and aestivation are two states of dormancy that animals, including hedgehogs, use to survive unfavourable environmental conditions, but they occur in response to different triggers and during different seasons.

Hibernation

Cold winters cause hedgehogs to hibernate. This is inactivity and sluggish metabolism. It helps them preserve energy when food is limited, and temperatures are too low for regular physiological activities. A hedgehog’s body temperature, heart rate, and metabolism drop during hibernation. This lowered metabolic activity allows the hedgehog to subsist on body fat until the weather warms up and food becomes available. In the fall, hedgehogs consume more to accumulate fat for hibernation.

Aestivation

Aestivation, on the other hand, is less common in hedgehogs but can occur in some species. It’s a similar state of dormancy to hibernation, but it happens during the hot and dry periods of summer. The primary purpose of aestivation is to protect the animal from extreme heat and drought conditions that can lead to dehydration and scarcity of food. During aestivation, animals also experience a decrease in metabolic rate and physiological activity, helping them conserve energy and water until conditions improve.

Conclusion

Overall, it’s important to know about hedgehog anatomy for many reasons, but mostly to protect their health and well-being, whether they live in the wild or as pets. Having a good understanding of their bodies helps you spot any signs of illness or discomfort, ensuring these unique animals get the care and attention they need. It also makes it easier to handle, feed, and care for them in general, encouraging a healthy lifestyle that is similar to how they live and behave in the wild.

FAQ

What is the hedgehog’s diet, and how is its anatomy adapted to it?

Hedgehogs are primarily insectivores, feeding on insects, snails, frogs, and various other small creatures. They have long, pointed snouts that help them forage and strong jaws with sharp teeth to crunch through exoskeletons and shells.

Can hedgehogs swim?

Yes, hedgehogs are capable swimmers. Their legs are relatively short, but they can paddle in the water. However, swimming is not a common activity for hedgehogs, and it can be stressful for them, so making a pet hedgehog swim is not recommended.

Are hedgehog spines poisonous or harmful?

Hedgehog spines are not poisonous and do not detach and embed like porcupine quills. However, they can still cause puncture wounds if not handled carefully. It’s also important to note that hedgehogs can carry bacteria like Salmonella, so proper hygiene is crucial after handling.

What is the lifespan of a hedgehog, and how does its anatomy contribute to its longevity?

In the wild, hedgehogs typically live for 2-5 years, but in captivity, they can live up to 8 years or more. Their spines provide a significant defense mechanism against predators, contributing to their survival. Additionally, their ability to hibernate helps them conserve energy and survive periods of food scarcity.

How do hedgehogs maintain their spines?

Hedgehogs engage in self-anointing or anting, where they lick or chew on something with a strong scent or taste and then produce frothy saliva that they spread onto their spines. This behaviour could help maintain the health of their spines, though the exact purpose is still a subject of study.

Is hedgehog rodent?

No, hedgehogs are not rodents. They belong to the family Erinaceidae, which is part of the order Eulipotyphla.

Leave a Reply